Company Going Private: Disadvantage Impact Calculator

Impact Analysis Results

Key Disadvantages Explained

Liquidity Loss

Shares become illiquid, making it difficult for employees and investors to cash out. The buyout price may be below market value.

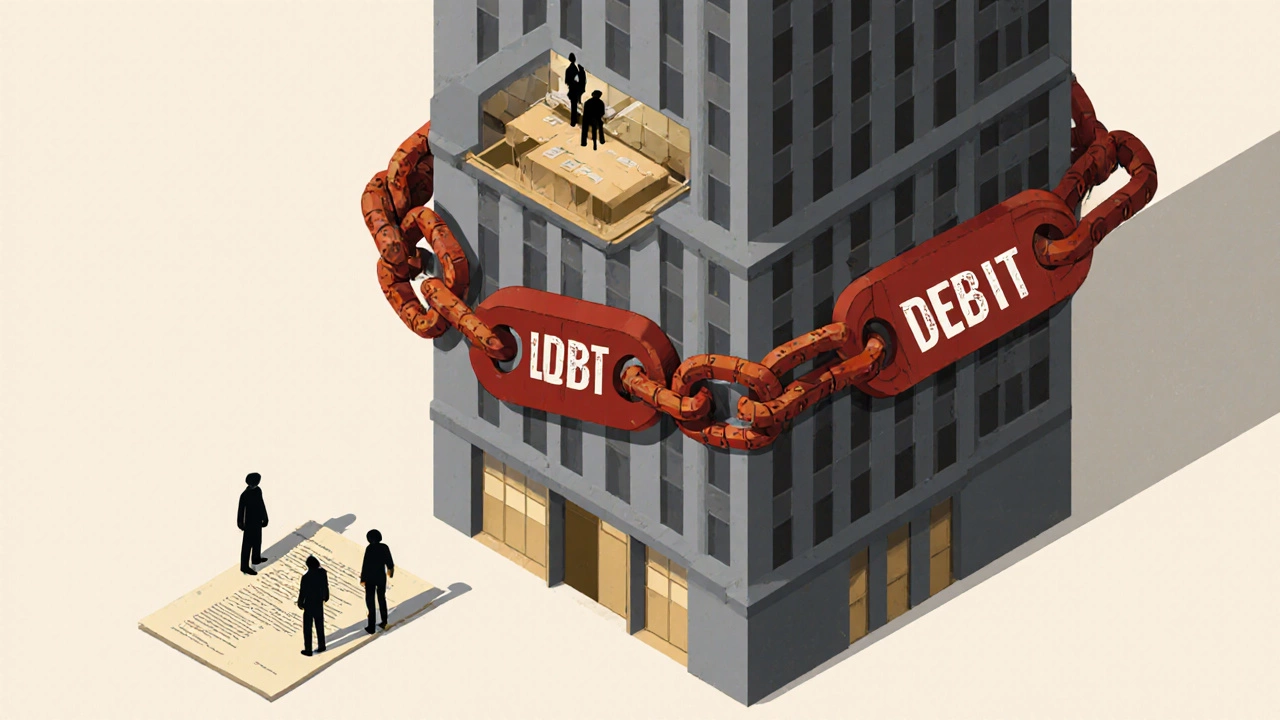

High Debt Levels

Buyouts often involve significant leverage, increasing financial risk and reducing cash flow for growth investments.

Reduced Transparency

Less regulatory reporting reduces stakeholder confidence and makes it harder to attract investment or secure loans.

Employee Retention Risk

Stock option cancellation or restructuring can lead to decreased morale and increased turnover among key talent.

Quick Takeaways

- Liquidity evaporates - shareholders can’t sell shares easily.

- Debt levels often surge to fund the buyout, raising financial risk.

- Transparency drops, which can hurt stakeholder trust.

- Management may face pressure to cut costs, affecting employee morale.

- Valuation disputes can leave former shareholders feeling short‑changed.

When a publicly listed firm decides to going private disadvantages are on many executives' minds. The move promises control, flexibility, and freedom from quarterly earnings pressure, but it also brings a set of hidden costs that can bite back hard.

What does “going private” actually mean?

Going private is the process by which a publicly traded company removes its shares from a stock exchange, typically through a buyout by private investors, management, or a private equity firm. Once the transaction closes, the company’s equity is held by a small group of owners rather than the broad public market.

The shift changes the corporate landscape dramatically. Public shareholders are bought out, regulatory reporting requirements shrink, and strategic decisions no longer need to appease distant investors. While freedom sounds great, the downsides can outweigh the benefits if they’re not anticipated.

Key Disadvantages to Expect

1. Liquidity disappears

Public stocks are prized for their easy convertibility into cash. When a firm goes private, that market disappears. Existing owners who retain a stake now hold ill‑iquid equity that can only be sold in a private transaction, often at a steep discount. This hampers the ability to raise capital quickly or to let employees cash out stock options.

2. Debt‑heavy financing

Most buyouts are financed with a mix of equity and large amounts of debt - a structure known as a leveraged buyout (LBO). Debt‑to‑equity ratios can jump from 0.5:1 in a typical public firm to 3:1 or higher after the deal. The resulting interest burden squeezes cash flow, leaving less room for growth investments or unexpected downturns.

3. Reduced transparency and scrutiny

Public companies must file quarterly reports (10‑Q) and annual reports (10‑K) with strict deadlines. Private firms can dial back on disclosure, which may please management but frustrates lenders, suppliers, and remaining shareholders who lose visibility into performance and governance.

4. Governance and oversight challenges

When a board shrinks to a handful of private investors, the checks and balances that protected minority shareholders often dissolve. Decision‑making can become concentrated, increasing the risk of self‑dealing, over‑optimistic projections, or neglect of long‑term strategy.

5. Employee morale and retention

Many employees are attracted to public firms because of stock‑option compensation and the prestige of working for a listed company. After a buyout, equity plans may be re‑structured, diluted, or cancelled altogether. If employees feel their upside is gone, turnover can rise, costing the firm both talent and continuity.

6. Valuation disputes

The price paid to take a company private is negotiated between buyers and the public shareholders. If the offer is perceived as too low, it can trigger legal battles, damage the brand, and create lingering resentment among former investors who may later become customers or partners.

7. Regulatory and compliance costs

Even though reporting requirements drop, the transaction itself triggers hefty legal, advisory, and filing fees. Antitrust reviews, securities law compliance, and tax structuring can cost millions, especially for cross‑border deals.

How to Mitigate These Risks

Understanding the downsides is the first step; taking proactive measures can soften the blow.

- Plan for liquidity: Include a provision for secondary market sales or a future IPO window to give owners an exit path.

- Structure debt wisely: Use a blend of senior, mezzanine, and equity financing to keep interest coverage ratios above 2.5×.

- Maintain transparent reporting: Voluntarily release quarterly updates to keep lenders and key stakeholders comfortable.

- Strengthen governance: Appoint independent directors, adopt clear conflict‑of‑interest policies, and hold regular shareholder meetings.

- Retain talent: Replace public‑stock incentives with phantom‑share plans or profit‑sharing schemes that align employee interests with long‑term value creation.

- Secure fair valuation: Hire impartial financial advisors, use market‑based benchmarks, and consider a fairness opinion to defend the price.

- Budget for compliance: Set aside a dedicated fund for legal and regulatory costs during the transition period.

Public vs. Private: Disadvantages at a Glance

| Aspect | Public Company Disadvantage | Private Company Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Liquidity | Share price can be volatile; shareholders can sell anytime. | Equity is ill‑liquid; exits require private deals. |

| Regulatory Burden | Heavy reporting (SEC filings, Sarbanes‑Oxley). | Compliance costs for the buyout transaction can be high. |

| Debt Levels | Typically lower leverage due to public market discipline. | Often financed with high‑leverage LBO structures. |

| Governance | Board must answer to many shareholders, slowing decisions. | Fewer oversight mechanisms; risk of concentrated power. |

| Employee Incentives | Stock options tied to public price; can be rewarding. | Equity plans may be restructured or eliminated. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do companies choose to go private?

They seek greater strategic flexibility, want to escape short‑term market pressure, and often aim to restructure without public scrutiny.

Can shareholders force a company to stay public?

Shareholders can vote against a buyout, but if a majority accepts a fair price, the transaction proceeds. Minority dissenters may receive cash payouts based on the agreed price.

What happens to existing employee stock options after a buyout?

Options are usually cashed out at the buyout price. Companies may replace them with phantom shares or profit‑sharing plans to keep talent motivated.

Is a leveraged buyout always risky?

Higher leverage raises financial risk, especially if cash flow projections fall short. However, skilled private‑equity sponsors use operational improvements to offset the debt burden.

How can a private company regain public status?

By preparing for an IPO or a secondary offering once the business stabilizes, demonstrates growth, and meets exchange listing requirements again.

Next Steps & Troubleshooting

If you’re weighing a go‑private transaction, start by assembling a cross‑functional team: finance, legal, tax, and HR. Run a stress test on debt scenarios, and draft a communication plan for employees and remaining shareholders. Should liquidity become a bottleneck after the deal, explore secondary‑market platforms that specialize in private‑company shares.

On the other hand, if you’ve already closed a buyout and are feeling the pinch of high debt or morale issues, consider renegotiating loan covenants, injecting performance‑based equity for key staff, or bringing in an experienced interim CFO to tighten cash‑flow management.

Remember, the disadvantages don’t have to be fatal. With careful planning and transparent governance, a private structure can unlock value that a public market sometimes stifles.